In my view, Bowtie is a unique company. It has an important mission tied to its customers’ everyday wellbeing. It is situated in a huge competitive sector that desperately needs innovation. And it is well positioned to succeed given its team, capital and traction.

I have since moved on to a part-time advisory role. And as I make these final edits, our team is celebrating crossing the HKD100M annual revenue milestone. A huge feat for a home-grown insurance tech startup. Kudos to the team.

In part 1, we will cover Bowtie’s mission and desired culture. Then in parts 2 and 3, we will dive deeper into how we implement that culture, and what product development looks like.

Building insurance with a mission

Bowtie started out an insurance company. In the future, Bowtie will grow to become a health and wellness company.

Insurance is a crowded space. The incumbents are corporate behemoths. Customers are well-educated, and insurance agents and sales people serve them well. This means that most people have bought insurance already, and we don’t have to educate the market. Instead we must constantly emphasize howBowtie is different, and why customers should trust us.

In other words, we can work less on telling people why they need insurance, and work harder on telling them why they need Bowtie’s insurance.

Early on, Bowtie’s founders had a strong sense of mission. When they started Bowtie, the mission was simple and memorable – “Make insurance good again”. The company roadmap had one item – launching our first medical insurance product. This was the income tax deductible “Voluntary Health Insurance Scheme” promoted by the Hong Kong government.

By the time I joined Bowtie, we had achieved this goal and more. By then, our roadmap had evolved. We wanted to make a greater impact our customers’ health and wellness.

Here’s Bowie’s top secret health and wellness master plan:

- We make insurance more affordable.

- We make underwriting and claims less painful and confusing.

- We create health programs for customers to stay healthy and demand less care.

Affordable pure insurance

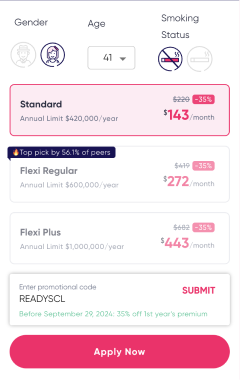

In Hong Kong, incumbents oftentimes sell insurance bundled with financial products, because that means greater revenue, and fatter commissions. So Bowtie would focus on pure insurance. We would surprise potential customers with how affordable comprehensive health insurance can be.

In this regard, Bowtie consistently builds price competitive products by omitting commissions, and including only product features and benefit coverage that we believe are tailored to customer needs.

Health insurance is important. Buy it when you’re young and healthy.

Ease and transparency build trust

Some insurers get a bad rap, but many of them actually provide decent products and customer experience. Since there are well known and loved household names in insurance, Bowtie would have to at least match, if not exceed the market in the quality of its digital experience.

In addition, we’d have to dramatically automate underwriting and claims operations with a skeleton crew. Software can’t solve every problem, but in this case Bowtie does have a leg up on our slower competitors. See Lemonade’s automation index.

In the early days, our differentiator was transparency. Every detail about our products and pricing is free and open for website visitors to access. No annoying lead generation forms that gate important information.

In the future, as we continue to invest in our in-house capabilities to underwrite applications, reimburse claims, and serve our customers, we think that we can deliver an experience that gets easier and more delightful.

Health

Bowtie wants to do more than pay for customer healthcare. We want to help them stay healthy. Preventing chronic disease before it’s too late is obviously great for customers. The big bet that we’re making here is that this arrangement will also be good for Bowtie’s bottom line.

Healthier customers are happier, more loyal, and likely to make fewer claims. This type of offering is generally called preventative healthcare. It’s a tough business to crack, but we believe in it enough to bet on it.

We launched a proof of concept in partnership with Gleneagles Hospital on the south side of Hong Kong Island. Together we launched an award-winning medical insurance rider, and we learned much from the experience. We also doubled down by building in-house healthcare expertise by opening a clinic downtown, in close partnership with JP Partners Medical.

Our passion for improving our customers’ health and wellbeing, and paying for medical costs with easy and affordable health insurance; that’s what moves Bowtie forwards.

But how does our team put this direction into action?

Let the team take ownership

Bowtie’s ambitious mission, in a hyper competitive industry and market, stems from the experience and expertise of our founders and leadership team.

Our founders used to advise insurance incumbents on digital transformation. More than one executive has launched digital insurance products from within incumbents before. Key roles are filled by industry veterans who understand the inner workings of the industry.

With a clear direction set at the top, the team can build. Our leadership also had a strong opinion on the type of team we wanted to cultivate.

“How do we want to build our products?”

“On a spectrum from dictatorship to laissez faire, where would you place the team culture we desire?”

After I joined, these were the first questions I asked our founders and engineering lead.

I had prior experience on both ends of the spectrum. So I explained that no matter their answer, we’d be able figure out how to build and ship product to achieve Bowtie’s desired outcomes.

I got a quick answer. We preferred to give staff a chance to develop a sense of ownership over decisions and actions at Bowtie. Guided by a clear direction, leadership had a strong opinion on where the company should go, and what the team should work on. But at the same time, it was also important to them we gave motivated employees the opportunity and resources to materially influence decisions, and even direction.

Why? Because we wanted to recruit builders and problem solvers to join Bowtie.

This isn’t a controversial point of view. Most companies these days, if not all, include some version of this message in their recruitment marketing. User-centric, design-led, engineering-driven, take ownership, influence stakeholders – these are some of the buzzwords that everyone uses.

So how did we execute this?

Contrary to the advice of internet gurus, I don’t believe there exists one best team setup and culture. Every organization is different. Every company has different complexity and a unique setup.

Instead, I believe that company leaders can design and implement a structure and system, where having plugged in all available resources, yields the desired behaviour from everyone. Just the right amount of influence from the right place. Just the right amount of ownership for the right people. Or close enough.

This in large part, is the product management function.

Here’s how we set it up at Bowtie:

- Small, nearly autonomous, cross-function teams; we just call them squads;

- A lightweight six-weeks agile development cycle;

- Goal-setting at the squad level, with a living Now-Next-Later roadmap.

Autonomous cross-function teams

When I joined Bowtie, our software team consisted of 8 engineers, 4 designers and 1 product manager. Everyone wore multiple hats. 2 engineers focused on infrastructure and developer operations, 1 designer focused on Webflow and WordPress, and another designer focused on user research. The rest of the team worked on day-to-day software design and development.

Every 4-6 weeks, senior team members looked at a long list of business and user requests together, to decide what projects would be picked up in the next sprint.

Like most early-stage companies, everything on the to-do list has an urgent deadline, or is a burning fire that needs putting out, or represents a significant revenue opportunity that can’t be ignored. The backlog is a mile long.

When prolonged, the team will feel like they’re always on the back foot playing catch up. This is not a motivating or productive place to be for long.

When your goal is to launch an MVP by a specific date, it’s easy for people to figure out how to get things done. You have a target audience, a set of non-negotiable bare minimum features, a basic launch plan, and a launch date. The goal is relatively focused.

But the day after the MVP is launched, things become more complicated. Users run into problems, request new features, and bring their friends to try your product. Internally, leaders and teammates have different opinions about what’s important to fix and ship. There’s never enough time for planning, for development, for quality assurance, for doing things by the book.

In this environment, the team is constantly pulled by competing and often opposing forces. It’s hard to get off the back foot.

But getting the team off the back foot is crucial for a mission-driven company. Only by keeping an eye on where it should be heading, can the team take control and build towards its mission.

Our solution was to give the software team more ownership. Specifically, more ownership over what the solutions we designed and built looked like. We would give them more influence over how to design solutions, and how to implement them.

Why? We had hired and continued striving to hire great people. Builders who were passionate about problem solving and serving the user well. Our big bet was that the whole team would move faster if we just trusted them to figure out how to solve the problems that needed to be solved. We decided to separate decisions on what problems to solve, from decisions on how to solve them.

We split the software team into 3 working groups, called squads. Inside squads, we increased squad members’ influence over what solutions would be designed and developed. At the same time, we encouraged collaboration with stakeholders outside the squad to determine what problems to solve and when to solve them.

In other words, if you were in a squad, you would influence what was built, and how it was built. If you weren’t in a squad, you could collaborate with squad members to influence what problems needed to be solved first.

Each squad would be setup with members who had all the necessary functional skills to achieve its goals. For example, if a squad was focused on building solutions related to our customer-facing web app, it would include designers and engineers familiar with that part of the product and related backend services. If a squad was focused on solutions related to marketing webpages, it might have a greater share of no-code designers and developers, working closely with marketers and a/b testing analysts.

With all the needed skills in place, a squad is now able to develop solutions in relative autonomy. Day to day, most teamwork and collaboration happens among squad members. When additional domain expertise, requests for support, and feedback was needed, squad members can then lean on stakeholders for support. For example, an engineer working on a claims feature who isn’t sure about how authentication works, will reach out to the go-to authentication expert for support and advice, but ultimately they will try to solve the problem themselves.

To keep collaboration quick, a squad need not be big. Something like Amazon’s two-pizza teams will do.

When we started running squads, several of the more experienced team members had to sit in more than one squad at a time. However, people thought this arrangement was unsustainable. Frequent context switching between squads would prove to be too costly.

In the long term, squads members will likely belong to only a single squad at a time, with the exception for exceptional teammates with unique domain expertise and above average productivity.

We’ll cover how we split up squads in part 3 when we cover goal-setting. In the meantime, Bowtie’s recruitment went into overdrive. Gradually, more engineers succeeded in passing our stringent recruitment process. The team started to grow.

Agile development without rigid frameworks

“The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organising teams.” – principle eleven of the twelve principles of agile software development.

I’m an agile minimalist. Agile is the style that I prefer, and I like the cherry-pick its best features to solve problems, without being too dogmatic about it. This has worked well for me throughout my software career.

Early-stage product management consists of coordinating actions across different teams towards a common product goal, given constrained resources and shifting priorities. When a company is first started, this is the founder’s responsibility. Later, oftentimes the CEO becomes too busy and brings on someone to take care of this.

This was the role that I found myself in joining Bowtie.

Earlier, we mentioned how we attempted to give squads autonomy over solutions. Within each squad’s scope, there was maximum freedom. Squad members were free to establish their own rituals. Some squads collaborated synchronously once a week, or several times a week, or never synchronously unless collaborating with outside stakeholders. They were free to determine how they wanted to work, what tools to use, and to what degree to follow established practices and templates.

But not everything was up to squad members to decide.

As a product leader, one of my responsibilities was setting up sandboxes for team members to play in. Each squad is a sandbox. Inside the sandbox, all the resources squad members needed (the sand, shovels, buckets) would be made available. But there would be rules to how one entered or exited their sandbox, and how sandboxes interacted with one another.

We adapted several approaches from Shape Up to Bowtie and our squads. Put together by Basecamp, their approach felt opinionated enough to be useful, but flexible and modular enough to customise. Unlike other common agile methods, we could avoid training the team in various strictly defined roles and rituals.

Here’s what we borrowed from Shape Up, and combined with our squads:

- Six-week development cycles, two-week cooldowns;

- Making bets, not backlogs;

- Exercise shaping opportunities for betting.

Six-week cycles, two-week cooldowns

Our experience with six-week cycles matches what Basecamp published online. Everything from solution definition, scoping, user research, prototyping, journey design, interface design, backend development, frontend development, testing to quality assurance – it all happens within one cycle.

This is why it’s important for squads to be relatively cross-function and autonomous. If they don’t have all the needed skillsets, things won’t move quickly.

Usually, squad members take the first 1 to 2 weeks to fully understand the projects that have been picked for the ongoing cycle. We trust squad members to determine what the solution direction is, how much effort is needed, and most importantly what needs to be cut from the scope.

It is common for projects to start off with several solution ideas, matching several prioritised problems that need to be solved. These solution ideas get narrowed down and prioritised. The prioritised ones are those that the squad believes will have a high enough impact within an achievable amount of time and effort. Squad members will make time to verify assumptions and de-risk solution ideas with outside stakeholders if needed. This is the moment squad members start to think through functional and technical requirements in detail. They also proactively complete needed internal communication with marketing, customer service or compliance within the cycle.

Different projects have different tasks, in different order. For example, for a new insurance product launch, a cycle may start by backend engineers collaborating with actuaries on setting up pricing and benefit items, while designers work with marketers to mock new content for landing pages. Or for a new user facing feature, designers may kick off a cycle by prototyping potential solutions for a quick round of usability testing, with a frontend engineer discussing what can or cannot be done based on their best estimate on effort.

The point is, instead of enforcing a strict order of doing things, we let squad members project manage themselves with the minimum amount of processes or checklists. Time and effort estimates are considered but don’t drive decisions.

The most important thing we enforce with cycles is a fixed start date and end date. Not everyone is able to make it by the end of 6 weeks and ship, but those who do get 2 weeks of cooldown when they get to work on whatever they think contributes to squad or team goals. In our time running six-week cycles, I estimate that around half of projects were shipped by the end of six weeks, a quarter were shipped during cooldown, and the rest had a launch that overflowed into the next cycle.

Most of the overflow stemmed from unexpected work, and unexpected time waiting for feedback or external approval. Given the goal of shipping fully functioning features by the end of each cycle, this situation is not ideal. However, I think that so far the benefits of giving squad members maximum project management freedom, has outweighed the benefits of micro-managing what happens each week during the six-week cycle.

At the end of each cycle, the whole team meets in a retrospective, discussing and enacting improvements for the next cycle.

So far, we’ve covered our decision to form small autonomous cross-function teams called squads. And we started to explore how we implemented a lightweight agile development process with six-week cycles. But that’s not all.

Making bets, not backlogs

If you spend too much time grooming and looking at your backlogs, you’re probably not very agile.

For decision making and prioritisation, I think backlogs are pretty useless. I almost never use a backlog to decide what’s important, or what gets built next. Great backlogs should help designers, engineers, and everyone quickly understand incidents and feedback that have already happened. They’re a great knowledge management tool. At best, a good backlog will inform the decision.

If you are deciding what to do based on a backlog, good luck.

At Bowtie, we run a ritual called Betting. We do it in a similar way to the way its described in Shape Up. 2-3 weeks before the start of the next cycle, a planning group collaborates on preparing projects that get taken into a betting meeting. The goal of this group is to use the betting meeting(s) to finalise which projects get bet on in the coming cycle.

This working group consists of a small number of product, design and engineering leaders who have the largest amount of influence in their respective functions.

This process isn’t closed off to the rest of the company. Everything in Bowtie is documented on Notion, so that anyone keen to contribute can do so asynchronously.

This working group also collaborates asynchronously. Depending on progress, calls are scheduled to allow for discussions on priorities, feedbacks, strategy, and resource allocation.

How we made our best every cycle was one of the hardest things to communicate with the company. Between each cycle is a circuit breaker. With the exception of only the most special cases, we don’t do any projects across two cycles. In practice, team members understand that they cannot leave unfinished items within a project to the next cycle. Instead, every cycle we revisit our priorities and resources from scratch. Just because a project was important six weeks ago, doesn’t mean that it will be as important six weeks from now. The circuit breaker forces the team to proactively prepare and plan for each cycle.

Before each cycle, we reset and make our best informed bet for what projects will make the greatest impact towards our objectives, given our limited manpower and resources.

Nobody in Bowtie can ever assume that something is “guaranteed to be shipped in the future”. This forces everyone to frequently revisit the company’s and customers’ goals, and make we’re always doing things that contribute to said goals. (We do make exceptions for projects for B2B customers and long term strategic work.)

Sometimes projects we bet on happen to be at the top of the backlog, but in my experience this rarely happens. Often our team members will find creative ways to address backlogged issues as part of a new project, or during cooldown. We are careful not to become servants of the backlog.

Exercise shaping opportunities for betting

We call the projects that we bet into cycles Opportunities. Shape Up covers some great points on what great shaping looks like. At Bowtie, shaping is an activity that is constantly changing and adapting to the people who are involved in it. That’s because everyone involved in shaping does it on the side, carving out time away from other responsibilities to do it.

Nobody works full-time on shaping at the moment, and we’re still experimenting with whether anyone should.

At Bowtie, a good Opportunity must have a very clearly defined set of problems that we think must be solved. Usually these problems are closely associated with a target audience who is experiencing them. To frame the problems, team members can consult metrics that measure user behaviour, or qualitative sources like reviews, call logs, and interviews. Often, team members may need to rely on the expertise of other company stakeholders to fully understand the problems.

Since there’s no formal Opportunities backlog, someone in the betting working group or the wider team usually proposes an Opportunity based on their personal observations of these product feedback loops.

When an Opportunity has its problems laid out, they are lightly prioritised based on their relevance to the squad’s goals and the roadmap. Really good Opportunities will then go further and include potential solutions to the problems. Shape Up does a great job suggesting ways to present potential solutions that help the betting process.

Ideally, we can take enough good Opportunities and a couple great ones into the betting process. This way, the betting working group can have critical conversations comparing which Opportunities have a greater chance of achieving our goals. In addition to problems and possible solutions, here are some optional items that team members frequently include in Opportunities:

- Future press release;

- Draft business model, revenue estimate or pricing;

- Target audience, and how to reach them;

- Competitive solutions, our unique advantages;

- Success criteria, measurable goals;

- Existing solution gaps, blockers, risks.

In reality, we have struggled with managing more than one really polished Opportunity per squad during the time I was at Bowtie. There are several reasons for this that the team is eagerly trying to address.

As mentioned, shaping Opportunities is not a full-time thing for everyone. Alongside day-to-day work, we just don’t spend enough time on shaping. I think this is reflected by the fact that we often have a pretty sense of what problems to solve, but we almost never have enough research done into the insights that we’ve collected, or potential solutions before putting solutions into production.

For leaders, finding capable teammates who want to take up shaping opportunities, and who have the skills to do so, is an incredible challenge.

At Bowtie, these individuals need not be product managers. Others can take up the responsibility of shaping Opportunities too. I personally enjoyed greatly working with Karl, a charismatic engineer who could rally the team behind Opportunities that he believed in, and do an amazing job in bringing the solutions to life.

In summary, Opportunities have clearly defined problems, and some possible solutions. As mentioned above, after betting is complete, squad members have 1 to 2 weeks at the start of each cycle to narrow the scope further, and determine the solution that they will pursue and ship by end of cycle.

In this format, we achieve the desired amount of agility during both betting, and in-cycle design and development. Just the right amount of influence from the right place. Just the right amount of ownership for the right people.

With the unending support of Bowtie’s sales and business development teammates, we managed to keep the cycle compatible with external deadlines as well. Projects for delivering enterprise contracts, and partnership collaterals are also bet into cycle. Due to the nature of the cycle, not everything that sales team wants gets built exactly as requested. But another way of looking at it is we are only ever building what’s absolutely needed and going to move the needle. This type of collaboration and compromise wouldn’t be possible without a huge amount of team-wide trust.

Goal-setting at the squad level, with a living Now-Next-Later roadmap

Our squad members are now enjoying a relatively high level of autonomy. At the start of each cycle, they pick up the Opportunities that have been bet, and they determine the most important problems to solve, and how to solve them. In close collaboration with squad teammates, and sometimes with stakeholders from other teams, they design, develop, test and ship new products and features to customers.

At the end of each cycle, we retro areas of improvement, and try our best to do better next round.

But there’s still one piece missing.

How do our Opportunities, and by relation what our squads are working on, relate back to Bowtie’s bigger picture mission and direction? How do we know that the Opportunities we are betting and working on, contribute to getting closer to our desired outcomes?

As a product leader, it was my responsibility to define these product outcomes, and the way we measure our progress towards these outcomes. At Bowtie, we use OKRs to connect squad activities with company direction. Each squad gets its own set of OKRs.

We have found the best way to set squad OKRs.

Just kidding. I don’t believe there’s one best way to set OKRs. But I do think there’s a couple things worth mentioning that shouldn’t be done.

A common mistake that startup founders and managers make is treating revenue as everybody’s primary OKR. For example, the objective is to grow revenue, and we’ll measure it by number of customers multiplied by the average revenue per customer. Revenue, top-line growth, profitability etc. – these business metrics are obviously important, but they are lagging indicators.

Lagging indicators are inappropriate for squad OKRs. Instead, leaders must brainstorm what are the inputs, that when improved will result in lagging indicator improvements. These inputs are what define squad OKRs, or product goal-setting for that matter.

Another common misconception is to try to make squad OKRs not overlap with each other. The fear is that there would be too many cooks in the kitchen, or the impact can’t be attributed to a specific project or team. My view is that making squads as autonomous as possible already solves this issue.

The biggest challenge for any product leader is to lead and facilitate a conversation among company leaders, to agree on what are the inputs that absolutely require investment by the digital design and engineering team to fix. It’s a delicate balancing act of resource management. And these decisions are reflected by what did and did not get written into the squad OKRs.

At Bowtie, the team would re-evaluate whether squad OKRs still made sense after every cycle once the existing version had run for three cycles.

However, leadership will run out of patience before running out of money.

If you told the rest of the company that every 6 weeks we re-prioritise everything, and review OKRs, and don’t maintain a solid backlog, every single team lead would riot. To give leaders and senior team members a clearer set of expectations on what’s coming next, we created and maintain a living Now-Next-Later style roadmap. This internal roadmap, in addition to communicating progress and what’s new, helps build trust in our process letting our people build the product.

Now shows the type of outcomes we are addressing at the moment. Next shows the stuff we are likely to bet on in the next few cycles. While Later are bigger picture ideas related to our mission and direction. These ideas won’t be built any time soon, but their existence on the roadmap helps team members make better short term decisions that line up with likely long term outcomes.

Since the relative timeframes are already bound by the cycle, we found that Now-Next-Later is a sufficient amount of expectation setting on the timeline.

With the company’s trust, the team can do their best work.

Minimum viable product management

Product managers at Bowtie strive to be both highly visible and invisible at the same time.

To support our squad members to make better decisions about how to solve different problems, our guiding principle is to shorten the feedback loop between user and squad member as much as possible. We strive to support initiatives that allow squad members to understand how the stuff they are building is being used by the intended audience.

Whether this is achieved by reported metrics, collated and cleaned user feedback, observed user behaviours, or something else. Our product managers actively seek to not be the messenger of feedback, or to reduce its incidence as much as possible. We strive to shorten the feedback loop between designers, engineers and user needs.

At the same time, product managers remain a highly visible source of direction and truth for all stakeholders. If there’s someone who’s best informed on finding the perfect balance among user needs, business goals, available resources, we hope that our product managers can be trusted to find that balance.

Taking everything mentioned together, here’s a snapshot of everything new that the team shipped in 2021 over 6 six-week cycles. Projects like performance and infrastructure improvements, bug fixes, partner or affiliate campaigns, compliance requests, design and developer operations, internationalisation aren’t included below, but I estimate they took up 15-20% of the team’s available time.

After Cycle 10, the team organised a hackathon and spent a couple weeks working on that and enjoying a well-earned holiday.

Over this time period there was no more than 10-12 staff involved full-time in Bowtie’s squads. This figure has grown since then. Over 2021, we more than tripled our recurring revenue and customer base, while holding churn steady and improving user satisfaction. We launched several new products, and are well positioned to capture market share in both insurance and health. Although we are just getting started, with the Mitsui partnership announced with our Series B, we are one step closer to achieving our mission.

Cycle 5 (2021 first cycle)

- Company HR managers can better submit accurate company information in group medical application – B2B, Insurance

- Employees of group medical customers can enrol into more than one plan type per company – B2B, Insurance

- Custom employee benefits onboarding flow for large enterprise customers – B2B, Health

- Product renewal on first year anniversary of BowtieGo products – B2C, Health

- BowtieCash rewards program now available for more products – B2C, Growth

- “4Protection” landing page campaign – B2C, Growth

- Education center to guide users how to choose the right type of insurance for themselves – B2C, Growth

- New individual applicant can better compare product options during the application – B2C, Growth

- New inputs, lists, interactions and quick actions for underwriting and claims officers in admin panel- B2C, B2B, Operations

- Launched first version of an instructions service to handle repeating tasks – Operations

Cycle 6

- Product renewal on first year anniversary of VHIS products – B2C, Insurance

- Launched first health rider to both new and existing customers, and allow users to redeem health services with BowtiePoints – B2C, Insurance

- New error handling, lists, interactions for new individual applicants during underwriting – B2C, Growth

- Members can submit claims for pre-approval by new partnership with third-party administrator (not launched because partnership postponed) – B2C, B2B, Insurance

- Handle different iterations of insurance products during configuration and claims approval – Insurance, Operations

- Admins can customise admin panel layout to accelerate personal workflows – Operations

- Settlement letters are automatically generated and sent to customer – B2C, Insurance, Operations

- Bowtie anniversary landing page campaign – B2C, Growth

- Launched new illustration library – Growth

Cycle 7

- Members can better file claims, find pending claims, view claims status in app – B2C, Insurance

- Rider customers with active BowtiePoints can activate their services with valid digital vouchers – B2C, Health

- Launch of Bowtie clinic landing page and generate digital body composition analysis report – B2C, Health

- Bowtie clinic staff can manage patient data and basic workflows for clinic opening – B2C, Health

- Launched group medical products with outpatient coverage together with new group insurance webpage – B2B, Insurance

- Members can submit outpatient claims in app, and they will be processed – B2C, Insurance, Operations

- Product renewal on first year anniversary of group medical products – B2B, Insurance

- Claims officer can better find claims documents, review insured life information, and generate reimbursement results – Insurance, Operations

- Finance officer can better approve and payout claims – Insurance, Operations

Cycle 8

- Sales can submit and approve discount schemes for individual customers buying group medical plans – B2B, Insurance

- Admins can create PDF document templates on admin panel to be reused throughout application – Operations

- Clinic customers can receive digital bodycheck reports and browse a health glossary for guidance – B2C, Health

- Users are recommended what products to buy together and get personalised premium estimates – B2C, Growth

- Customers can adjust their sum-assured amount for products that have that option, and certain product restrictions were reduced – B2C, Insurance

- Customers can find a history of changes made to their in-force policies – B2C, Insurance

Cycle 9

- Launched first enterprise plan tailor-made to a large customer’s specification – B2B, Insurance

- Replaced old customer referral program with new program that worked with new products – B2C, Growth

- User can better understand reasons behind exclusions or premium loading during application – B2C, Insurance

- Accident insurance underwriting questions reduced by 75% – B2C, Insurance, Operations

- Users can better discover, retrieve and activate health vouchers in app – B2C, Health

- “Debug” landing page campaign – B2C, Growth

- Replaced telemedicine provider with new provider and streamlined flow – B2C, B2B, Health

- Admins can better create, search, manage health vouchers in batch – Operations

- Introduced justifications to underwriting decisions – Operations

Cycle 10 (2021 last cycle)

- Launched Bowtie’s first medical insurance product with full coverage Bowtie Pink – B2C, Insurance

- Admins can create, edit, test, underwriting question flows for different insurance products and save versions inside admin panel – Operations

- Users can better submit outpatient claims – B2C, Insurance

- Users can save payment details to their profile to be reused for claims settlement – B2C, Insurance

- Preorder page for new experimental health product for parents with kids – B2C, Health

- Revamped company homepage – Growth

Bowtie is hiring builders to engineering, design, and all roles. It is a hybrid remote company, with teammates distributed in several time-zones. It operates an excellent café and clinic in downtown Hong Kong. Reach out to Sara Choi or I.